In 2022/23 we travelled for one year through South America.

Sadly not with an EV but with an ICE 4×4. The reasons for not using an EV can be found here. And if you are interested in the trip report take a look here.

Nevertheless, we learned a lot of things on this trip that will also be useful for future overlanding trips with EVs. In this post, we will share the most important findings.

Vehicle

Choosing the right vehicle for a long international overlanding trip is very important.

The vehicle has to be robust and in perfect condition. The roads are often quite challenging with lots of severe corrugations.

Before starting the trip you should definitely check everything and have a fresh service. Personally, I wouldn’t start this kind of trip with a very old car with lots of mileage, and also not with a just-released very new car that could still have some initial bugs.

The car we used in South America was a proven design, that has been on the market for many years, but it was only 6 months old and had run less than 5,000 km. We had zero problems with our car in the 12 months, while other overlanders we met with older vehicles constantly spent their time in workshops to fix some problems.

If you want to be able to reach most of the interesting places 4×4 and high ground clearance are a must. It doesn’t have to be an extreme offroader, just 20 cm of ground clearance and a simple two-motor setup (for an EV) are sufficient for 99% of the interesting tracks.

On overlanding trips, you sometimes have to cross rivers.

Normally they are not very deep (unless you plan to explore Iceland). Therefore, a wading depth of your vehicle of about 30 cm is often sufficient. Check your operation manual about the maximum allowed wading depth and don’t exceed it. If nothing is specified, I would never drive in any water depth exceeding half of your wheel size.

Your car should also be large enough to provide some limited interior living space in case of bad weather (which will happen sooner or later on a long trip). It is highly recommended to find a setup where you can comfortably spend a day inside the car, eat and drink there, and do some work on your notebook. If you can sleep inside your car it’s an advantage but it’s not a must in my opinion. More about this topic in a later post.

Very important is easy access to most of your equipment. If you have to empty half of the car to be able to reach certain items it quickly gets frustrating. You need some storage concept where often-used items are easily accessible and seldom-used items are packed further away. Robust plastic storage boxes like the standardized Euro-Boxes are a good choice for interior storage builds. But don’t buy the cheap thin ones from supermarkets. That’s a lesson we learned in South America. They might be good enough for home storage, but on the harsh conditions of an overlanding trip, they survived just a few days. For the next trip, we have already bought a couple of Euro-Boxes in different sizes.

Driving on corrugations will eventually lead to loose screws. Check important screws every day during the trip and tighten them if necessary. This is especially important for accessories like roof racks and hardtops.

Another lessons learned in South America: scratches on the side of the vehicle are inevitable, especially if you plan to explore narrow and overgrown offroad tracks.

Whether this matters to you or not, depends on how old your vehicle is, if you plan to sell it after the trip, and how important the look of your car is to you. If you hate the idea of having scratches all over the door panels I would recommend getting your car wrapped or putting a paint protection film like XPEL on both sides of the car. I still haven’t decided whether I will do this with my next car or not.

I will make a separate post in the next weeks about choosing the right EV for international overlanding trips. A very interesting and probably controversial topic.

Tires

The tires are probably the single most important piece of equipment on an overlanding trip.

They are responsible for how safe you can drive under all conditions. In addition, they are a decisive factor in whether you will be able to reach a certain place or not. Furthermore, they are also crucial whether you can fully enjoy your trip or spend many hours changing tires, looking for workshops, or trying to find new ones.

For an overlanding trip, I would highly recommend getting AT (All Terrain) tires.

They are far more robust than standard road tires and offer a good grip on all kinds of road conditions like wet paved roads, gravel, sand, mud, and rocks. Yes, you will lose range using AT tires on an EV, but it’s worth it in my opinion.

In an ICE vehicle, depending on the planned destinations, I would probably even choose an MT (Mud Terrain) tire due to its even higher robustness. But for an EV the much higher rolling resistance and higher weight of MTs and therefore additional range loss is just not acceptable.

AT tires can differ quite significantly between brands and types. Some are more road-focused, built only for the occasional gravel road and some are more offroad-focused based on an MT carcass with a slightly milder profile.

We started our trip with nearly new Pirelli Scorpion AT tires. A type that is often favored by OEMs due to its excellent performance on wet roads and low noise (for an AT tire). But this comes at a price. The Pirelli tires didn’t survive our first serious offroad track in Argentina. We had more than 12 punctures in just one tire and most of the tread blocks were seriously damaged.

It’s a good tire if you spend most of your time on paved roads but for challenging overlanding tracks it’s just not robust enough. Well-known tires like the BF Goodrich AT or the Cooper S/T Maxx are clearly better choices. If possible get one with a 3-ply sidewall but not every brand offers this option.

Since on an overlanding trip you typically drive rather slow and carefully handling qualities of a tire on dry and wet roads are less important than robustness.

I would never ever go on an overlanding trip without a full-size spare tire. Sadly, most current EVs either have no spare tire at all or just an inflatable emergency tire as an option. The only exceptions are large trucks like Rivian, Hummer, or Cybertruck.

This means you have to buy a spare tire separately and find a place to store it in or on the car. After some punctures in South America, we even decided to carry a second spare tire (just the tire without the rim) to be on the safe side. Since most EVs have limited space this likely won’t be possible with an EV. Instead, I would recommend carrying a tire repair kit in addition to a full-size spare tire. That’s what I will do on my next trip.

This is trivial, but verify, that you have all the necessary equipment in your car and the knowledge and experience to change a tire by yourself. Especially if your car has no spare tire from the factory it often has also no lifting jack from the factory.

Equipment

A very typical problem on longer overlanding trips is, that you carry too much stuff that you don’t really need.

We had definitely too many clothes on our trip. Doing laundry every two weeks is easy. If you are in a remote location wearing the same pair of jeans or the same fleece jacket for two weeks doesn’t feel awkward. If you have one pair of spare trousers, one additional warm top, a rain/wind jacket, a couple of t-shirts, and enough underwear and socks for two weeks it is normally sufficient even for months-long trips.

An additional down jacket was very useful for these cold nights at high altitudes. I’ve used one of these ultra-thick expedition down jackets from North Face. It kept me warm on these cold nights in Patagonia and also at 5000m on the Bolivian Altiplano.

Check out for sales. I got the jacket for 1/3rd of the original price and it’s great.

You can find some additional remarks regarding cooking and photography equipment under the specific sections.

Cooking

We had a rather basic cooking setup on our trip. We used a very small Soto trekking stove, a couple of pots, pans, plates, cups, bowls, a knife, and some forks and spoons.

The Soto uses standard threaded screw-on gas canisters (C100, C300, C500, CA500), normally filled with a butane/propane mix.

They are available nearly everywhere in the world. In South America, they can be found even in very remote places (often in hardware stores). In Europe and the U.S., they are available from brands like Primus, Optimus, and Coleman in different sizes. It’s neither the most economical nor the most ecological setup but it works worldwide. I will stick to this solution for my next trips.

We had an MSR water filter on our trip but never used it.

The main reason was, that we spent a very long time in Patagonia where the water quality is extremely high and needed no filtering. Depending on your destination a good water filter system can make sense.

We had a very small Engel fridge (14 liters).

It’s nice to have a fridge for stuff like eggs, milk, butter, and cheese but it’s not obligatory in my opinion. Of course, if cooking is an important part of your overlanding experience or you often eat meat I would recommend a fridge.

We went on average every third day to a local restaurant or had some street food. For us, it’s an important part of overlanding to try out the local food and dive into the local eating culture.

Therefore, for the other days, stuff like pasta, vegetables, fruits, coffee, bread, and cheese were sufficient for us. Neither of this needs to be cooled.

With an EV I will probably skip the fridge on the next trip to reduce weight, gain additional storage space, and optimize the vehicle range.

Sleeping

Since we were 3 people and just had a small pick-up truck, sleeping in the car was no option for us. We used a mix of renting apartments, using hostels, and sleeping in our tents.

In some places in the world, apartments are really cheap. In Argentina, we often paid less than 20€ for a fully equipped apartment for three people. In South-East Asia it’s similar. While in Europe, Australia, or New Zealand you often pay more just for a single campsite.

The advantage of occasionally sleeping in an apartment or hostel is, that you get much more in contact with the local people and learn more about their life and their culture. Just as an example in San Pedro de Atacama in Chile we had rented a small cabin for a few days and were invited by the owners to join their traditional family barbecue where the food was cooked in a hole in the ground. A great experience.

Therefore, the combination of apartments/hostels and camping worked very well for us.

If you plan to camp regularly on an overlanding trip choosing the right tent is very important. Regarding the topic of ground tents vs. rooftop tents, I will make another blog post in the future. Let’s focus on ground tents for now.

If you plan to explore places like Patagonia or Iceland the tent should be as stormproof as possible. We often had wind gusts above 100 km/h. Cheap tents would immediately break down under these conditions. I’ve seen enough destroyed tents in my life after heavy storms.

We used two Hilleberg tents on our South America trip (for three people), a Keron 4, and a Soulo.

The Keron 4, despite being a proven tent for many expeditions in Antarctica and Greenland, was just sufficient for the strong wind gusts in Patagonia. It survived but it definitely needed all the available ropes and tent pegs to secure it.

In the same conditions, the Soulo didn’t move at all and would have probably survived even without any pegs. The smaller the better in stormy weather.

On the other hand in bad weather and on longer trips a bit more interior living space in a tent can also be a big advantage. I’m still not sure what’s the best compromise here.

Our camping chairs weren’t used very often. Therefore, next time I would bring only very small and light ones. We had one from Helinox on the trip which fit perfectly to this description and worked flawlessly on the trip. The larger chairs will stay at home next time.

Regarding sleeping mattresses, I would recommend getting some of the thicker ones for more sleeping comfort. The additional weight is a challenge on backpacking trips but not on vehicle-based overlanding trips. We used mattresses from Exped and Therm-a-Rest. Both worked equally well. Just the time and effort needed to fill the mattresses every evening was a pain in the ass. After the trip, I bought a small electric pump for this job. Since I have no experience with this pump I won’t recommend it, but I will definitely try it out on my next trip.

For sleeping bags, each of us used a combination of two sleeping bags on this trip, a thinner one for warm weather and a thicker one for cold weather. And the combination of the two at the same time for very cold nights like on the Lagunas Route in Bolivia where we had around -20°C during the night. This combination worked very well. We used down bags from Western Mountaineering. Some of them were already 35 years old and still worked very well. This somehow justifies the very high price of the WM products.

Border crossings

The first border crossing on a new continent is always a bit stressful and frightening. But after your second or third crossing, you know how the wind blows.

Border crossings can be time-consuming but they follow always a very similar procedure: First immigration of the country that you are leaving, then customs of the country that you are leaving, then immigration of the country that you are entering, and finally customs of the country that you are entering.

On average the whole process took about one hour in South America, but there are countries where this can take much longer.

If you find a border control that insists that your papers are not correct (although you know that they should be ok) then just try a different border crossing or if the next one is too far away return at a different time of the day when the next shift is working. This often helps to solve the issue.

Bringing fresh food, especially fresh meat or honey, from one country to another is often forbidden. Read the rules before the border crossing and always declare that you have potentially not allowed food items in the car, especially if the rules are not 100% clear or need some interpretations (which is nearly always the case). That way they will just confiscate items that are not allowed but you won’t get a fine.

Money

Credit cards work very well nowadays in most countries of the world (exceptions are countries like China and Iran, but that’s a very specific topic).

It’s always good to take a couple of different credit cards. Sometimes they get blocked for no real reason and it takes days to unblock them. And sometimes they get stolen or lost (therefore it’s important to store them in different places).

It’s also a good idea to use different types of credit cards (VISA and Master and credit and debit). In some countries, the fee for using a debit card is much lower compared to using a credit card. Some ATMs just accept credit cards, some only VISA, and some only debit cards.

Often the limit per card and day on an ATM is very low. Therefore it is very useful to have a couple of cards to consecutively withdraw money out of an ATM.

I had 5 different credit cards with me on my South America trip: Barclays Visa, Barclays Master, Hansa Visa, Visa from my home bank, and a Wise debit card.

Barclays Visa and Hansa Visa were my main cards. They are free and they don’t charge any additional fees for usage outside of Europe. The Barclays Master and the Visa from my home bank were just for backup and were used only once on this trip. The Wise debit card (also free) was used whenever a debit card was needed.

To avoid blocking of credit cards due to unusual activity it’s best to inform the CC provider about the duration of your trip and the countries you plan to visit. I did this for my Barclays card after they blocked it in the first few days in South America. After the call, I never had a problem again with unjustified blockings.

In addition to credit cards, it makes sense to take at least some cash. We had a mix of US$ and €. In South America, it’s important to have clean new 100$ notes without any marks. They are widely accepted and will give you the best exchange rate. Small notes and notes with marks are more difficult to change and often lead to very bad exchange rates. Despite what some people say it was also never a problem to change 50€ notes.

In some countries like Argentina, you can get better exchange rates compared to using an ATM by sending money to Western Union and picking it up from a local WU office (often integrated in large supermarkets).

Photography

We took a lot of photography equipment on this trip: 3 main cameras, 6 lenses, 1 backup camera, 2 drones, 4 smartphones, and 3 tripods.

A backup camera definitely makes sense on a long trip to remote places. Halfway through our trip, the Sony RX10 of my daughter had some serious problems. It was impossible to find a similar camera as a replacement in Patagonia. Luckily, it never stopped working completely.

The same is true for drones: every drone will fail. Either due to some technical issues or due to pilot error. It’s only a question of when. On our trips to Norway and Iceland in the past, we lost a drone on each trip. In South America, a single drone would have been sufficient but I was happy to have backup. Getting a replacement would have been impossible in Patagonia or the Altiplano. And even in large cities like Buenos Aires or Santiago de Chile to get an identical drone would have cost us twice as much as in Europe or the U.S.

Getting the newest smartphone before a long trip can make sense. The camera is often significantly improved with every generation. And a smartphone in addition to a serious camera is a very useful tool on these kinds of trips, especially for documentation of interesting situations and for cities where you don’t want to take out your big camera. As written in the safety section taking an additional old smartphone is useful in unsafe areas. For example, in Valparaiso and in Buenos Aires I only used my 5-year-old phone.

A small notebook is highly recommended. It is very useful for checking your images or videos, backing up your images to additional external drives, and sorting, selecting, and processing some of the images during the trip. I used a 14-inch Macbook Pro. The relatively small screen was sufficient for this application.

For data backup, I had two additional hard drives stored at different places in the vehicle (while the notebook was in a third place). If you can afford it, I would recommend external SSDs for backup due to their higher mechanical robustness (and better resistance to high altitudes). SSDs are not good for long-term storage of images but as a backup drive for important images for a couple of months while driving thousands of km on extremely corrugated roads they are perfect. We had no fails of the notebooks or the SSDs on our trip.

What would we change next time?

I had two DJI Mavic Air 2S drones with me. They have good image quality for a relatively low price but they have a weight of around 600g. Next time, I would only bring drones with a weight below 250g on any overlanding trips. There are far fewer restrictions for these lightweight drones in many countries of the world. The DJI Mini 4 Pro now uses a very similar sensor as my Air 2s and has a weight of 249g. This will be my choice for the next trip.

Another lessons learned was, that we took too many pictures on our South America trip. Combined we had shot more than 600,000 images on the 12-month trip that needed to be reviewed, processed, and selected. This is a huge effort that will probably take up to two years and can lead to frustration. I would love to use my energy and time for planning my next trip but instead, I still have to focus on the images of my past trip. I didn’t enjoy this situation and something has to be changed for the next longer trip.

My plan is to shoot less, even if this means that I sometimes will miss important situations.

I often shot different perspectives, different focal lengths, and different exposure values of the same subject or landscape to be able to later choose the best version. This approach is just not practical if you are many months on the road. On the next trip, my plan is to shoot fewer images of the same situation, consciously risking that the composition is not optimal or the exposure is way off.

In addition, my plan is to process as many images as possible directly on the trip and not afterwards. Not sure if this will work. In South America, it sadly didn’t work at all. One reason for this is explained in the next paragraph. But maybe the occasionally long charging times for an EV on a wall plug will help.

One problem we encountered on the trip was, that we needed electricity regularly to charge all our devices. While we camped for two weeks in the Torres del Paine Nationalpark in Chile we had no electricity at all. By using our car we barely managed to daily charge the batteries of our cameras, drones, and smartphones, but it was impossible to charge our notebooks during that time (except for charging in a restaurant once or twice). This means review and backup of images during that period was impossible which was not good.

As a solution to this problem, I will next time carry a larger power pack in the car. I bought an Ecoflow Delta 2 Max with 2048 kWh. It is about the same size as our Engel fridge which I won’t take next time (see the cooking section). How good this solution will work remains to be seen.

Charging all the devices regularly via the HV battery of an EV would be no option for me since it would impact the range of the vehicle way too much, especially in remote places where charging the EV is often also a big challenge.

Navigation

For many routes across the world, Google Maps works very well as the main navigation tool. It has two drawbacks: First, the more remote the track is, the less reliable is Google Maps, and second, its offline mode sucks. Offline navigation is a very important feature on an overlanding trip. There are many areas around the world without any cell phone coverage (see phones and communication section).

Both problems can be avoided by using Maps.me (in addition to Google Maps).

Maps.me has a very good offline mode and also covers most offroad tracks and even hiking trails. But it provides just far less information about the surroundings, infrastructure, and interesting highlights of a place than Google Maps. Therefore, the combination of these two tools is a good choice.

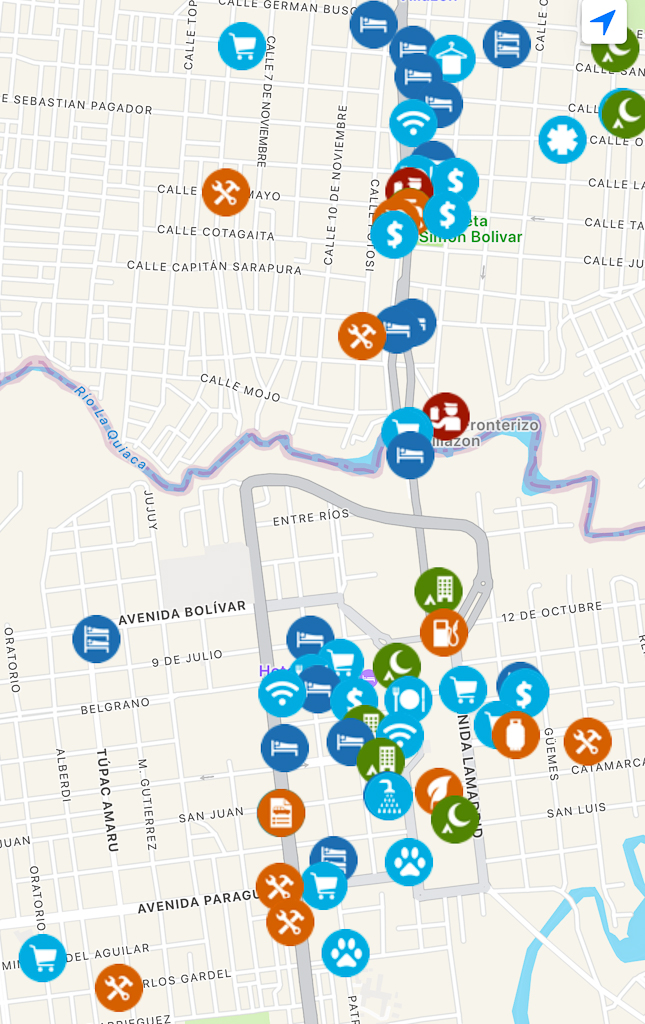

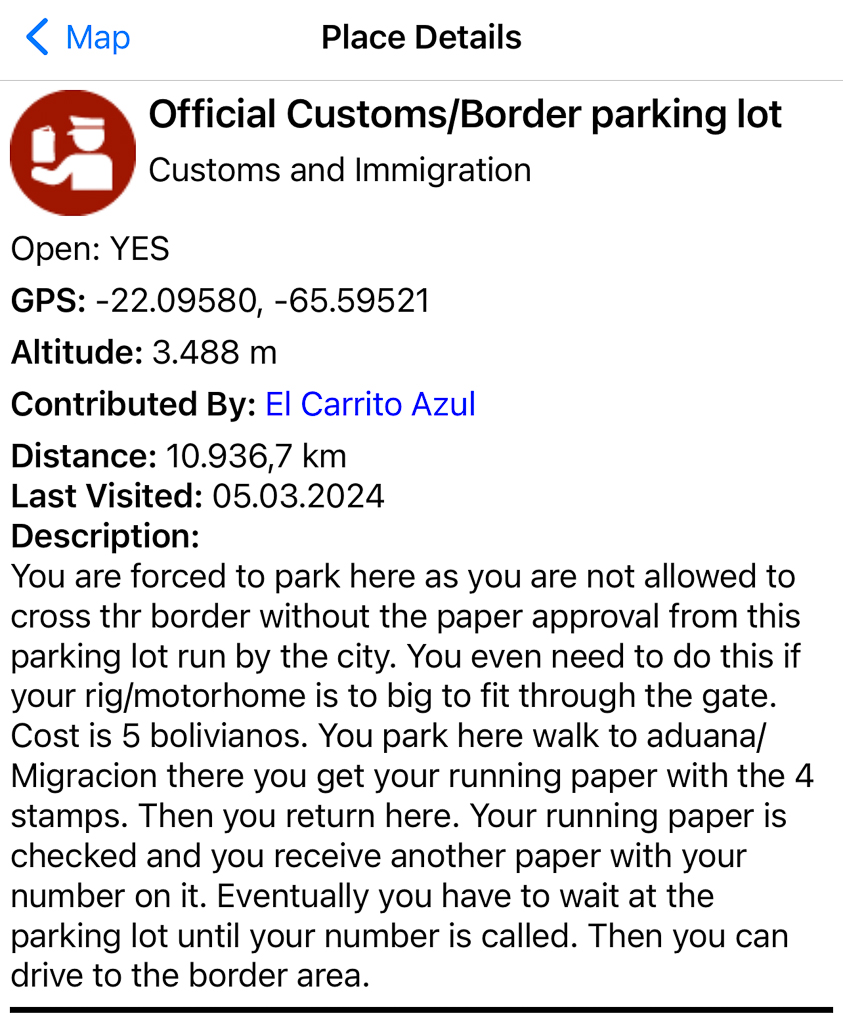

Another important tool for navigation is iOverlander (available as a smartphone app and web application). iOverlander is very important for finding certain infrastructure like ATMs, drinking water, workshops, etc.

It is also good for finding additional info about places you would like to visit, like opening hours and entrance fees. Last but not least iOverlander provides excellent information about border crossing procedures.

The information in the tool is crowd-based and therefore far more up-to-date than any guidebook or blog.

Safety

Safety is always a concern on overlanding trips. I have lots of experience in the wilderness. Therefore I’m not really afraid of nature or animals. I know how to deal with it. If you are less experienced inform yourself before the trips about topics like dangerous animals, floods, extremely high and low temperatures, volcanic eruptions, and so forth. There are lots of good books, websites, and YouTube videos about these topics.

In case you are stuck somewhere with your vehicle you should know the basics about self-recovery and carry the necessary equipment. For this topic, there are also many resources available explaining this in detail. I never had a winch on my cars, but on more serious trips I have at least some sandboards, a shovel, and a recovery belt in my vehicle. And in case this doesn’t work carry something for emergency communication (see section phones and communication).

My top three main fears on an overlanding trip are vehicle break-ins, getting robbed, and getting sick (in that order).

By far the best tool to avoid vehicle break-ins and robberies is iOverlander. There is a warning icon and if you see this near your location or planned destination you should definitely read the associated text. My guess is that probably 99% of the robberies and break-ins always happen in the same locations. Therefore if you know them, 99% of the risks can be avoided.

For example, in Chile, there are two cities where you have to be extra careful: Valparaiso and Calama. Due to the detailed information about what had happened there, we went to Valparaiso by bus, avoided the port area completely, and did not walk around at night.

In Calama, there is an extremely high risk of vehicle break-ins at a certain supermarket parking lot. If you absolutely have to buy something there then at least one person has to stay in the car. We didn’t stop at all in Calama and just drove through the city to reduce the risk.

In addition, we always parked our car in larger cities only in locked or guarded parking lots. Sometimes they are not easy to find, and sometimes they are not cheap. But in our experience, it is worth the effort and money.

Another strategy to avoid robberies is to leave any wristwatches at home (and of course any kind of jewelry if you normally wear this), never use expensive camera equipment in dubious places, and in high-risk areas only use a very old spare phone instead of your main phone (both for photography and navigation).

Regarding becoming sick the only thing you can really do is carry some emergency medication and know how to use it. Talk to your doctor about what makes sense and read some books about this topic.

High Altitudes

If your planned route involves high altitudes (like most routes in South America and Central Asia) there are a couple of additional things you should keep in mind.

First, acclimatization is key. And there is no good shortcut around it. It takes time. On the Altiplano it took us around 4 weeks until we felt comfortable at 5000m.

During the acclimatization phase, it is a good idea to drink lots of water and regularly measure your blood oxygen level with a pulse oximeter. If the value is too low and/or you are feeling severe symptoms of altitude sickness (like headache and dizziness), leave this place and drive to somewhere at a lower altitude. I would do this if my level is below 90% (at an altitude between 4000m and 5000m) for at least half an hour and a couple of measurements. But I’m not a medical doctor and therefore this is not a medical advice.

Personally, I would not take any medication like Diamox prophylactic against altitude sickness. It covers some of the symptoms and due to this leads to additional risks.

In some South American countries, it is very common to use coca in high altitudes. It is available as leaves (which can be chewed), tea, or as candy. We tried the coca-candy and it really helped to reduce the symptoms. Coca-candy is available in most stores in Bolivia. For the same reasons as mentioned above about Diamox, I would use it only when I know that I will be at this altitude just for a short time.

If you plan to buy coca products please verify that they are allowed in the country where you are. For example, bringing your Bolivian coca-candy to Chile could get you in trouble.

An ICE vehicle will lose at least 50% of its power in high altitudes. In addition, with modern European or U.S. diesel engines, you often get big problems with clogged particle filters in this environment.

Luckily, an EV has neither of these problems and is therefore perfectly suited for high altitudes.

Phones and communication

Your local SIM won’t either work on a different continent or you have to pay a very high roaming fee.

Therefore it’s best to get a local SIM for your phone in each country and register your phone if needed. In some countries your phone has to be registered (Chile) and in some just the SIM (Bolivia). If you don’t do this your phone/SIM will be blocked. The people selling you the SIM often don’t tell you this.

WhatsApp is a very important communication tool in South America. Every booking is done via WhatsApp even in big hotels or workshops. Hardly anybody answers emails.

Another benefit of WhatsApp is, that there are several Overlanding WhatsApp groups where travelers exchange important information in real-time. This is extremely useful. Here you can find a list of all WhatsApp groups for overlanding.

If you are not already using WhatsApp it’s highly recommended to install it for overlanding South America.

Don’t expect to have cell phone reception everywhere. In Patagonia and the Altiplano, there are large areas with absolutely no coverage. For these situations, an alternative method of communication is very useful, especially in the case of an emergency.

We had two additional devices on our trip in South America: An Inmarsat satellite phone and a Garmin inReach Mini. The inReach was mainly used on hiking tours because it is extremely small and lightweight. It has a somewhat cumbersome method for two-way text communication (via the Iridium satellite network) and an emergency button for calling a search and rescue team.

The satellite phone always stayed in the vehicle. It allows full communication like a normal GSM phone (but only slow and very limited data transfer). We didn’t need it in South America, but we have already used it in the past in Namibia to solve problems with our vehicle.

I would at least take one of these two emergency devices on my next trip.

If you buy a new satellite phone compare the coverage of the network with your planned destinations. Only Iridium provides a nearly global coverage, all the other providers have certain limitations. Inmarsat for example doesn’t work in both polar regions due to their geostationary satellites.

Exchange with other overlanders

We learned on our trip that direct exchange with other overlanders can be extremely helpful.

You will often meet them at the (on iOverlander) recommended overnight spots or at the well-known highlights along a route. Nearly all of them are very happy to have a chat with a fellow overlander and exchange some tips.

Other very good options are the above-mentioned WhatsApp overlanding groups and the direct exchange via Instagram. Some people also use Facebook groups for this, especially on the Panamerica. But we have no personal experience with FB.

A very special exchange with a fellow overlander in South America was our meeting with Arkady Fiedler in Chile.

Arkady is not only a very experienced overlander from Poland, he is also the very first person who ever drove across the whole of Africa with an electric vehicle, a Nissan Leaf. Driving successfully from Capetown to Poland with that car (non-4×4, very small battery) was quite an accomplishment.

Since I’m following him on Instagram I know that he was also on a long road trip in Patagonia driving a very similar route as we but in the opposite direction (and also this time not with an EV). After a chat on IG, we found out that our ways would cross in Puerto Rio Tranquilo and we arranged a meeting there.

Arkady is an extremely nice guy. He is extremely enthusiastic when he talks about his EV expeditions. His stories about crossing Africa with the Nissan Leaf were absolutely fascinating and I learned a couple of new things. Most importantly, if you have to drive a section that exceeds your maximum range and there is absolutely no chance for any kind of electricity along the way your only option is to drive slow, very slow, like 20 km/h slow. That has helped him in extreme situations to significantly extend his range to numbers that are normally just impossible. But driving for the whole day (or even a couple days) at just 20 km/h is very challenging both for your body and mind. I really hope that won’t be necessary for my future trips. But at least I know now that this is an option to get out of a difficult situation.

If you want to learn more about Arkady’s expeditions take a look at his YouTube channel or his Instagram account. And I can really recommend reading his e-book about his Africa trip (available in English on Amazon).

Duration and daily stages

Our experience was that after 3 months, we were feeling saturated due to all the new impressions every day. Therefore my recommendation would be to either limit the trip to a maximum of 3 months or plan longer breaks of at least 1-2 weeks at one place after a longer time on the road. Otherwise, you will feel sooner or later burned out. That’s very important to understand and to plan accordingly.

And don’t plan to drive too long distances in a too short amount of time. On good highways, 500-1000 km in one day can be possible, even with an EV. But on challenging offroad tracks, we sometimes needed 8 hours for just 70 km. My recommendation would be to plan not more than 4 hours of driving time per day on average on a long overlanding trip. If you have enough time for your trip definitely less than that would be even better.

Charging infrastructure

Although we had an ICE vehicle in South America I was still checking regularly the charging infrastructure for potential future EV trips. High-speed chargers are still extremely rare.

Sometimes Type 2 AC Chargers are available even in remote locations.

But often they are in a dubious condition and look like they haven’t been used in a while.

Some of them were mounted in really obscure locations. In Ushuaia for example the charger was placed in the main entrance to the parking garage of the biggest shopping center in this area. If you would use the charger you would completely block the entrance to the parking garage for all cars.

I have absolutely no idea why they put it there.

Wall plugs are nearly always available and often the only option for charging. So be prepared for sometimes long charging times if you plan to cross South America with an EV.

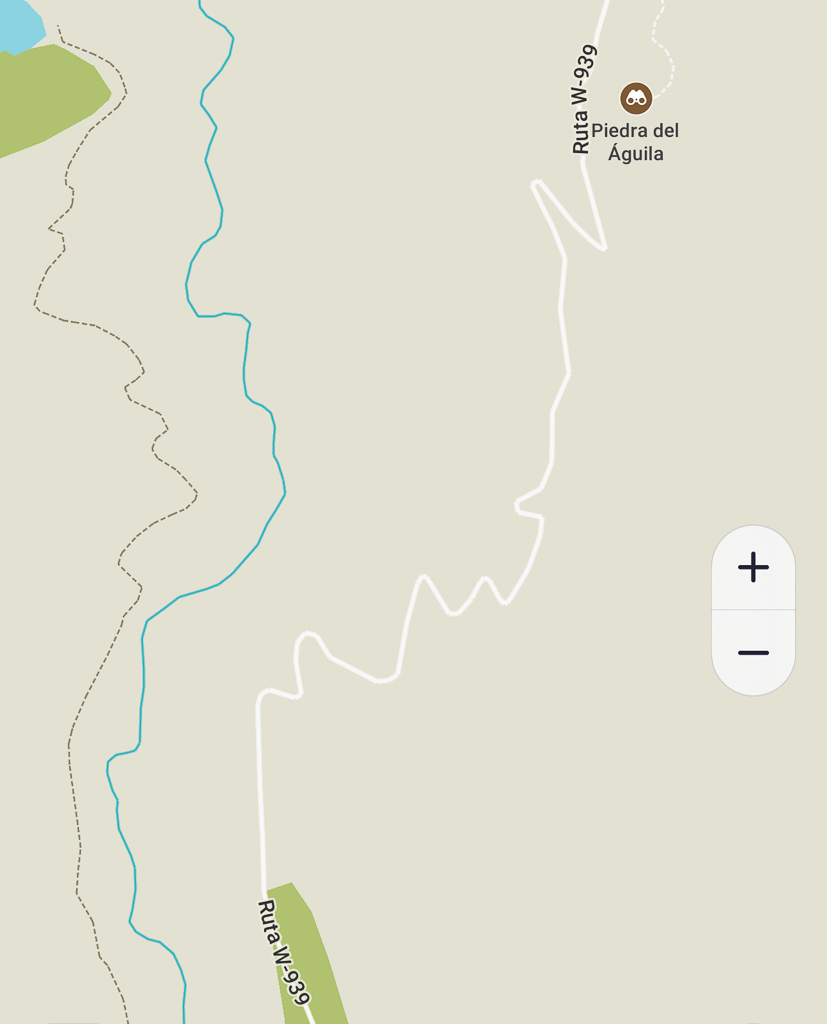

Some remote offroad tracks are longer than 400 km without any kind of electricity and are currently just not possible to explore with an EV. Some examples are shown below.

But 98% of all tracks we have driven during the 12 months in South America would have been possible with an EV.

Altogether an expedition through South America with an EV seems to be feasible. More about this in one of the next posts.

If you have any additional questions about international overlanding feel free to ask them in the comments section under this post.

One thought